Learning and Unlearning: Bringing an Anti-racist History Block to Richmond Waldorf School

Waldorf education is designed to meet the needs of the developing child, intellectually, socially, emotionally, and physically. Each class teacher has freedom to adapt the curriculum to the needs of their class, and this year our 8th grade teacher brought a new, and intentionally anti-racist lens, to the study of history of our country and our city.

We sat down with our 8th grade Class Teacher, Ms. Amey to learn how she has created an 8th grade history block that reframes the story of America to confront the hard realities of the founding of our country, and to highlight courageous individuals in the Richmond area (and beyond) who worked tirelessly for racial and social justice. In a Waldorf school, the class teacher begins with their class in Grade 1, and continues with them for several years, often all the way through their 8th grade year.

We’ve adapted and edited the conversation between Letitia Amey, Class Teacher, and Valerie Hogan, Enrollment & Marketing Coordinator, from November 2020.

LA: This is the first time that I’ve really been able to do this work so directly with the students in our school. The Waldorf history curriculum doesn’t focus on current events until 8th grade, so I’ve been really looking forward to finally bringing these subjects to my class, as I knew they were ready to explore them.

When the Black Lives Matter protests started happening in our city back in the Spring of 2020, I felt like it was my job to start to bring these current events to the students in a way that felt appropriate for them. We began the dialogue with questions like, “why are we protesting?” “What is the history of our city?” “How do you all feel about what is happening in our city right now?”.

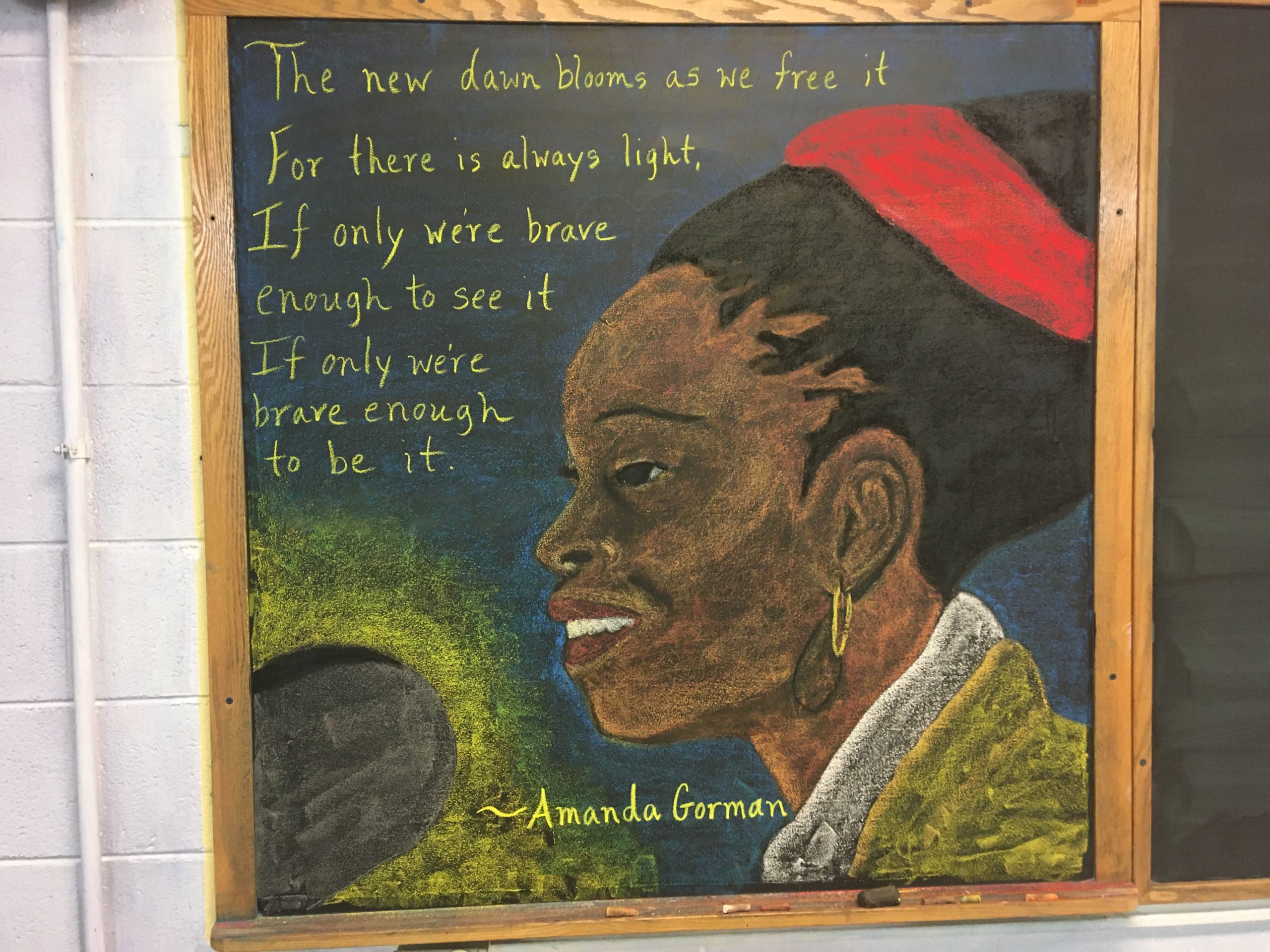

My hope is that by introducing these topics and stories to the class, they will feel inspired in some way to do something with them later on and that it will empower them to make a change. So much of this history is really hard, so I want to make sure they also walk away from the lessons with a feeling of hope.

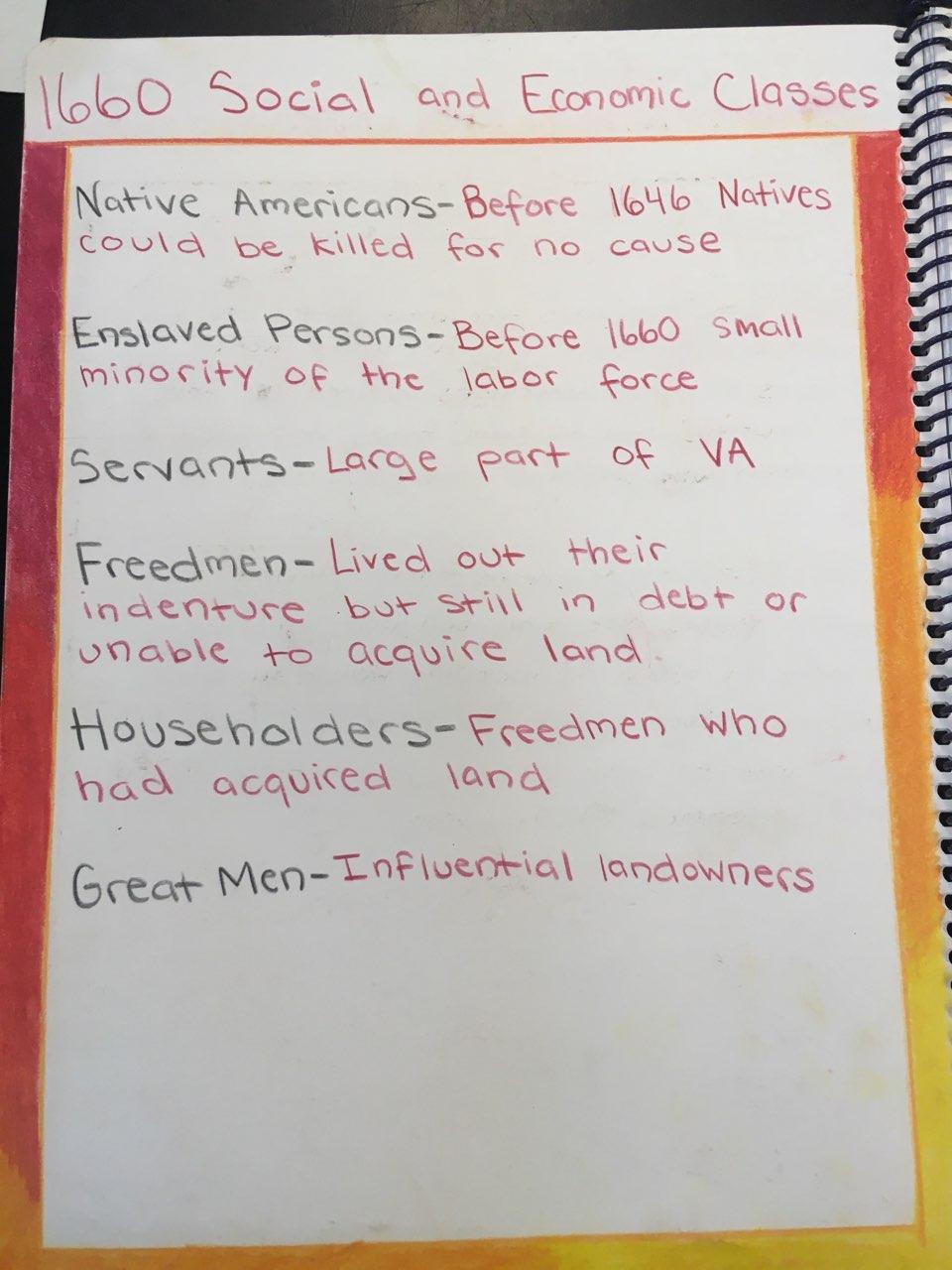

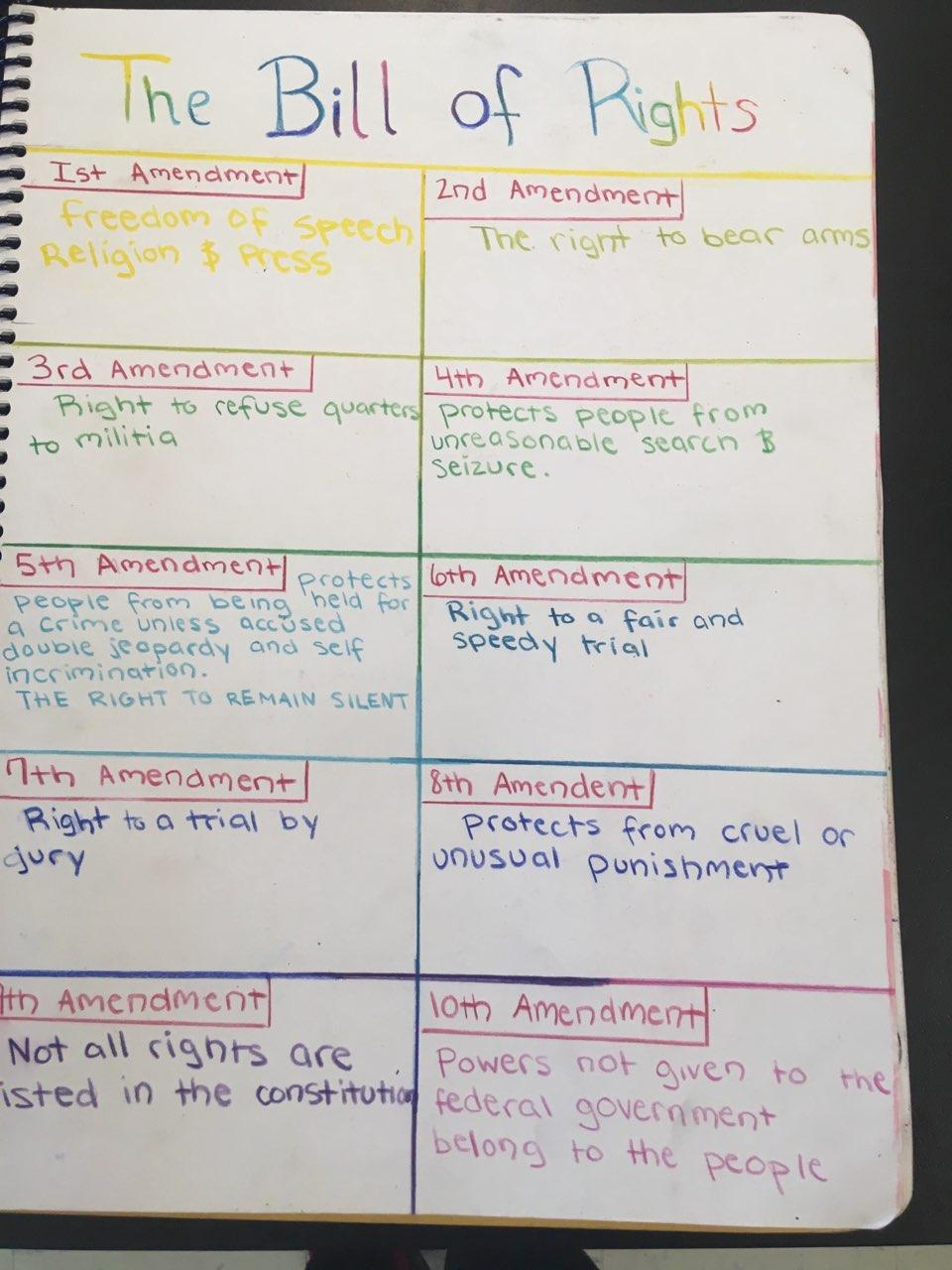

We started this block by talking about our government system. We studied the Constitution and how it was formed. The students immediately started noticing the flaws in our system and the inequities at work everyday in our country.

To reframe our understanding of this nation’s history, I’m giving them our history, from the perspectives of people we don’t usually hear about. People like Gabriel Prosser, an enslaved man outside of Richmond in the 18th century, and the incredible rebellion he planned. We have also been critically considering the biographies of the white male heroes that we see throughout the history books, and asking ourselves, “What were they doing this for? Was it for the common good?”

My hope is that my students will take hold of something that was meaningful through our lessons and carry it forward into their lives. I hope that this way of learning about history makes a difference in the way they think about the world around them. It is so important for them to understand the past in order to make sense of the present and make a difference in the future.

VH: We say that Waldorf is an education for the future, and to see that teachers can bring their personal passion is really powerful. How did you do the research for this?

LA: I read a lot of books this summer, and used many resources from [my Waldorf Teacher Training]. The topic of diversity was an integral part of my intensive through Antioch University [Waldorf teacher summer intensive training], and I gained a lot of resources from other teachers, and from the women who lead the course. I used Howard Zinn’s book, and a selection of books that told the African-American, Indigenous Peoples and Latinx versions of the history of the United States. I also used a wonderful book titled, Unhealed History of Richmond, which has been a great resource as well. My students just read a chapter on the slave trade here in Richmond. They learned about Lumpkin’s Jail and its horrible operation. There are so many details and perspectives that are left out of traditional history books.

VH: One of the things I have gained from my own unlearning is that ordinary people can go through great adversity and struggle for what is right, and maybe they won’t see that ripple in their lifetime, but it will live on and that ripple effect can do something powerful. I think you are starting that ripple in your students, too.

LA: Yes, that is my hope, for the students to see that individuals who face insurmountable challenges can still make an impact for positive change in the world. That’s much of what they’ve been hearing throughout this history block. We had a parent who offered to share an amazing autobiography of a Native American, Samson Occum. This parent luckily for us, did a lot of work on her dissertation around Native American untold stories. Samson was a Native American who was educated by one of the New England ministers and ended up opening a boarding school for Native American children. In his autobiography, he points out that he felt used for much of his life. When he started his own school, he decided to teach his students in a different way. Ultimately, the importance of preserving his culture throughout his lessons was a significant takeaway for my students. We were so fortunate to have a parent with so much knowledge of this topic share her passion and research.

VH: What type of work are students producing in the classroom around this intense history block?

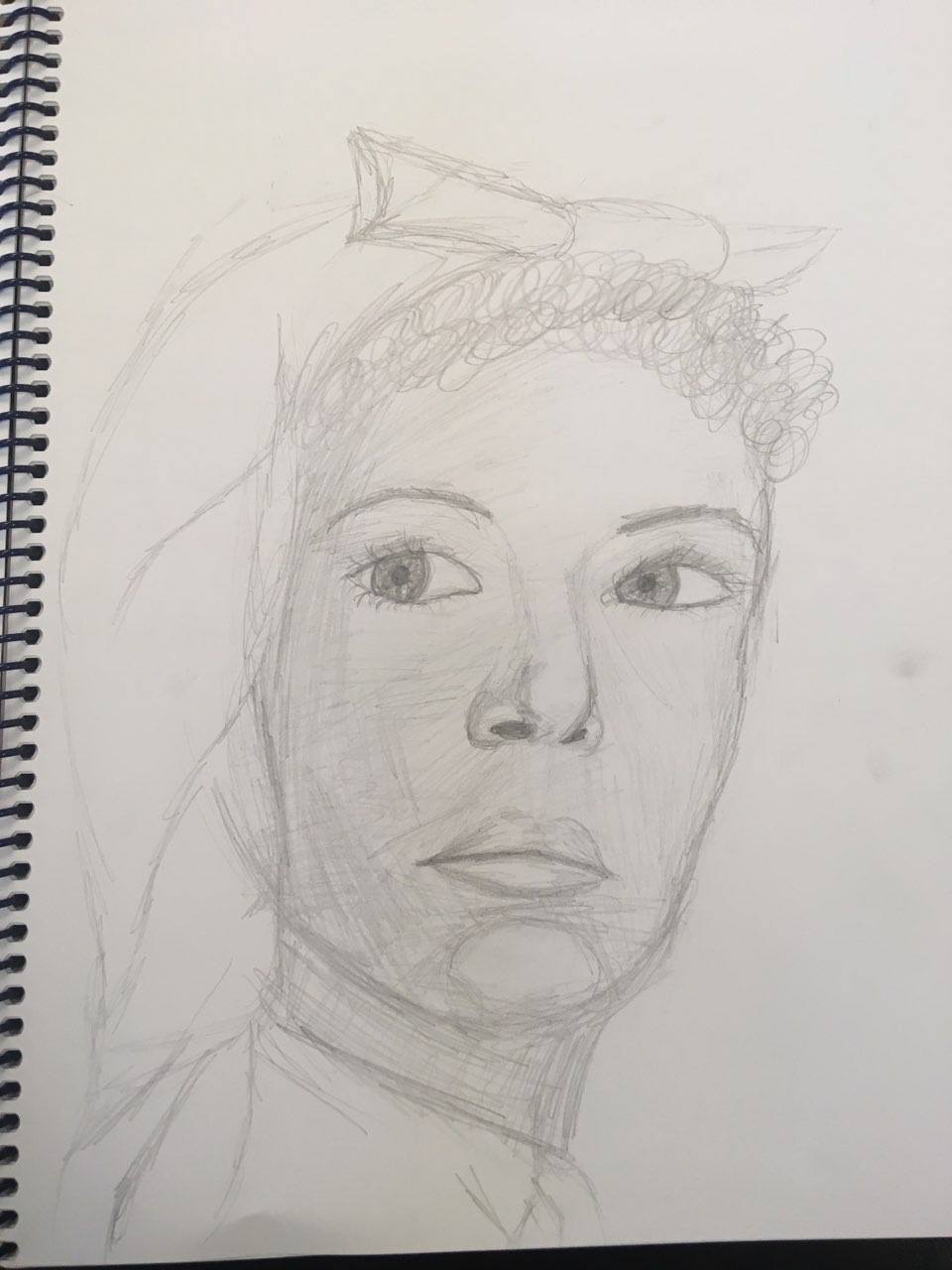

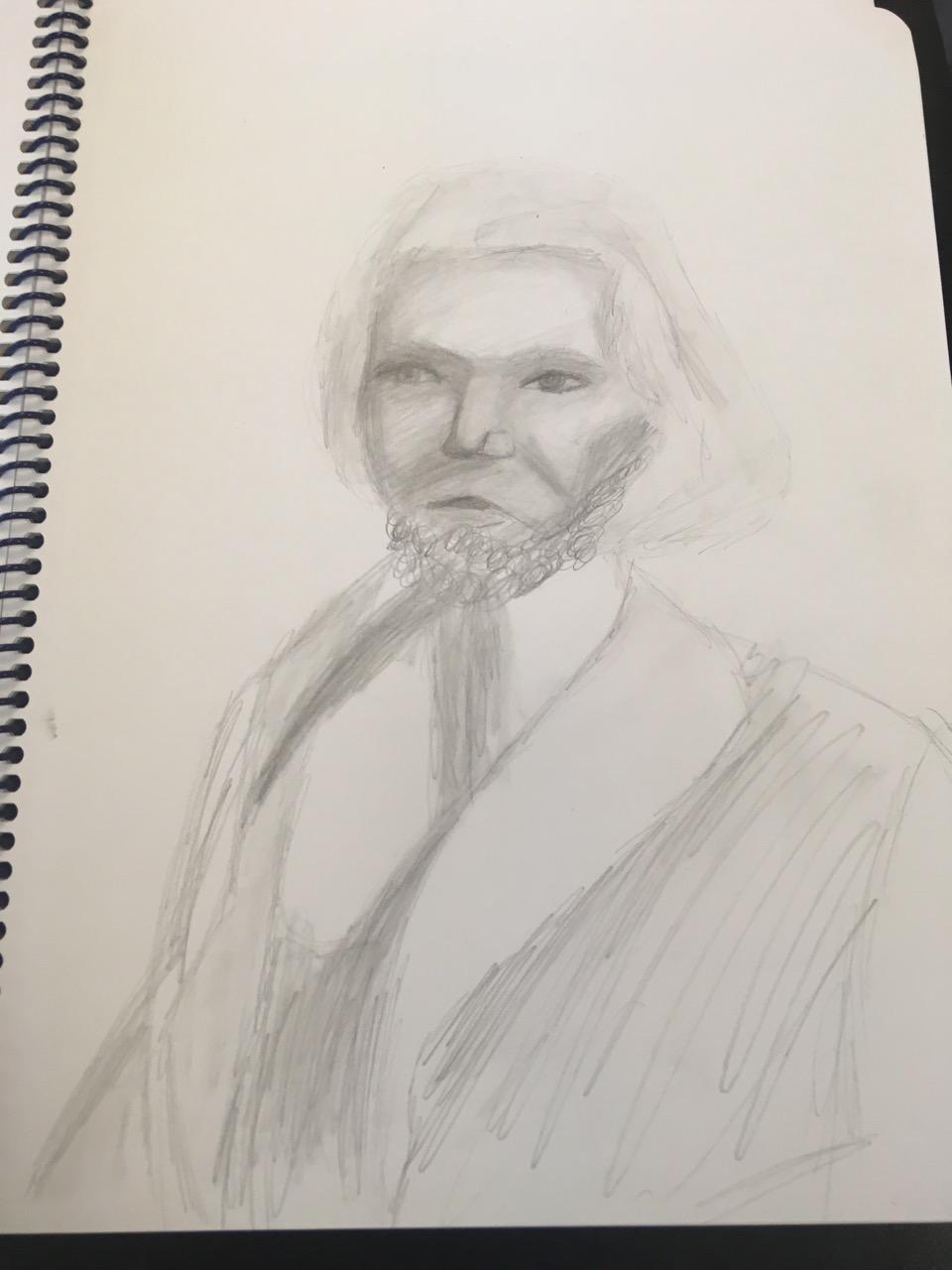

LA: For main lesson work, they’ve been working on individual compositions. It can be difficult for an 8th grader to articulate these enormously complex thoughts. Timelines have been a really helpful learning tool, especially as we move into studying the civil war and the events leading up to it. Some students are very comfortable sharing their opinions while others are processing the material more inwardly and through their writing.

VH: What’s next in this study for your students?

LA: Well, we will have one more History block that will carry us through to modern times. We’ll take a tour of different parts of Richmond in the spring, walking along the slave trail, visiting the African burial grounds, going to the home of Maggie Walker and learning about our city’s history in a more experiential way.

VH: This work is so critical for our school and our students, especially with this pandemic and seeing the inequity in education. I feel that we have a responsibility to do better, and unlearn some of what has been ingrained.

LA: I completely agree. I’m glad that we’re doing this work in earnest, and I’m so grateful to have the RWS Diversity Equity and Inclusion Committee supporting us and doing their work as well. My hope, as we move forward, is to have someone who is trained come and talk to our students. I’m opening the conversation, but to have someone with the tools to continue that conversation will be crucial..

VH: Thank you, Letitia. You are an amazing teacher and your dedication to your students does not go unnoticed!

LA: Thank you, Val. It’s been an honor to walk through this study with my students.