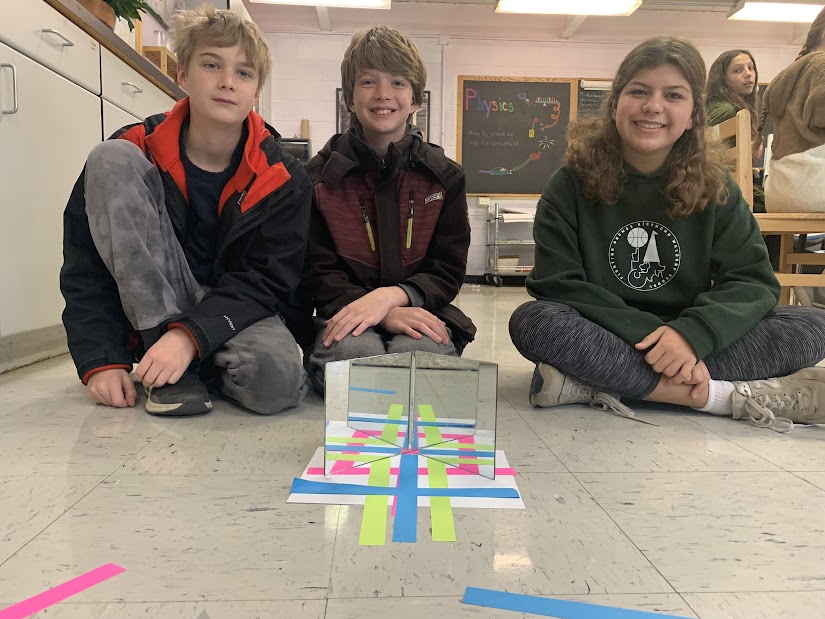

Learning is Multi-Sensory. Teaching Should Be Too.

Children learn in many different ways. That’s why it is so important for teachers to bring concepts through multiple senses. In Waldorf schools we teach science through stories as well as outdoors in nature and in the lab. We move, build, and even bake and eat our math. We teach literature through theater. We sing our history and languages. We teach this way so that our curriculum reaches more children, more deeply, in a way that they love and remember.

Waldorf Education in the Age of AI

How would you design an education system that helps students flourish in the face of changes to the nature of work, brought on by Artificial Intelligence (AI)? The rise of ChatGPT and other AI large-language models have brought this question to the forefront of parents and educators’ minds. Waldorf education is uniquely focused on developing children’s creativity, cultural competency, imagination, and original thinking. We believe that we set our students up for future success by teaching students how to articulate their own diverse viewpoints and understanding of the material. In a future where AI-generated content relies on recombining existing […]

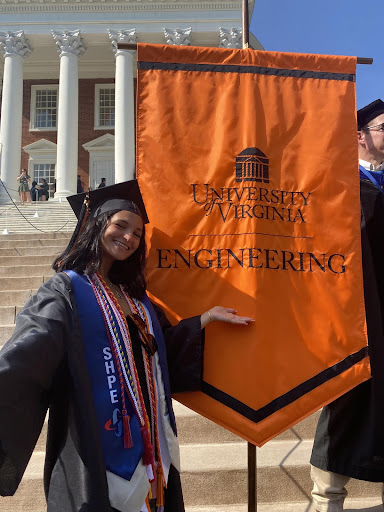

How Waldorf Students Stand Out

With an increasingly competitive college admissions process, grades and test scores are no longer the final deciding factors for students to be accepted into the colleges of their choice. Applicants need to find ways to distinguish themselves from the crowd. Waldorf students stand out in many ways from their peers. These Waldorf graduates bring a unique perspective, set of experiences, and skill set. The Waldorf approach, which incorporates the arts, outdoor education and hands-on learning into academics, helps our graduates stand out as individuals. They are curious, creative, confident, and experienced in working with their peers, their hands, and […]

Waldorf Education: A Thoughtful Approach to Homework

Too often, homework becomes meaningless busywork that stresses and overwhelms students and their families, crushes creativity, and has little impact on children’s future success. In Waldorf education, we take a thoughtful, age-appropriate, and balanced approach. Homework is not introduced until later and is always focused on meaningful assignments to foster creativity and developing a deeper understanding of the subject. Assignments will often include an artistic or project-based component that connects to the theme being studied.

Letters from the 3rd Grade Farm Trip

The developmental phase that third graders experience is called the “nine year change” and practical activities such as planting, harvesting, and animal care provide purposeful work that help the third grader feel part of the world around them. This is all thoughtfully woven into the 3rd Grade Waldorf curriculum, and culminates with a highly anticipated right of passage: the Third Grade Farm Trip. Here at Richmond Waldorf School, our students travel to a working biodynamic farm in the Hudson Valley of New York for a week long immersive experience. Their teacher, Ms. Dawn Pollard, sent these lovely and inspiring letters to those of […]

Excelling in a New Field is Nothing New for Alum Stephanie Gernentz

RWS is incredibly proud that our former student, Stephanie Gernentz, RWS Class of 2014, is featured in the Spring 2023 edition of School Renewal, a journal for Waldorf education.

Waldorf Education & the Adaptability Quotient: Educating for an Uncertain Future

With increasingly rapid changes in the nature of work, employers are interested not just in intelligence and social skills, but in an employee’s adaptability quotient–their ability to adjust to new challenges with flexibility, curiosity, courage, resilience, and problem-solving skills. In Waldorf education, we deepen rigorous academics by integrating art, outdoor education, music, theater, practical work, movement and hands-on learning. The depth and breadth of the Waldorf curriculum challenges students and develops crucial capacities that will help them adapt and thrive throughout their lives. The premise of a Waldorf education is to provide a learning environment that promotes independent […]

Theater Develops Creativity, Empathy, and Confidence

The performing arts help children develop a range of beneficial life skills, such as quick thinking, problem solving, and building self confidence. Theater strengthens empathy by asking a child to embody what their character is feeling and experiencing, and putting on a play also requires students to work as a team. In Waldorf education, students are involved in class plays and musical performances every year. We see the wide-ranging positive impact on our students and the powerful boost to their self confidence that the performing arts provide. In Waldorf schools, each grade does a play every year, and […]